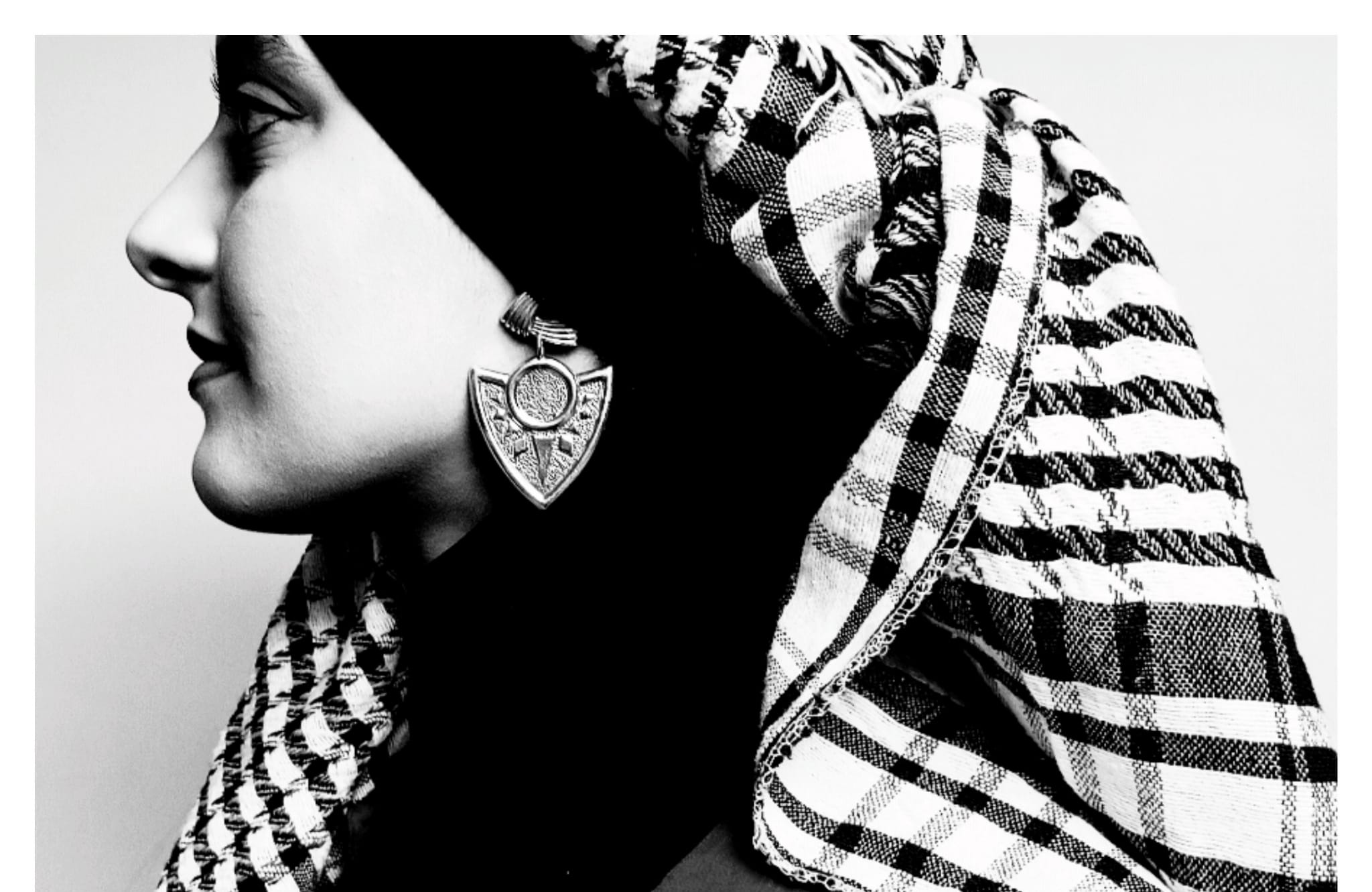

The veil and my voice: Open letter to tomorrow's society

How can the voices of veiled women be heard in a society that still considers them a minority ?

Dear future,

I am writing to you today because I no longer want silence to prevail. My political commitment is not a slogan or a program: it is my way of living in the world without apologizing for it. I come from Dijon, and I am writing to you from Mainz, where I am participating in the Europe Convergence project. Here, I am learning that talking about oneself is already a public act. Wearing the veil does not mean silencing my ideas: it means bringing them to light, calmly and stubbornly.

For me, being committed means defending dignity when society commodifies it. It means refusing to let people debate about me without talking to me. It means saying that equal opportunities only make sense if they include those who are labeled “minorities” in order to marginalize them.

I am writing to you because I have learned, sometimes the hard way, that political commitment is not limited to the speeches of elected officials or votes at the ballot box. It lives in our bodies, in our gazes, in our forced silences. It is born every time we decide to say, “Enough is enough.”

My commitment is about equality. Not equality proclaimed on paper. Not the kind that is written into laws and forgotten in the streets. Equality that is lived. Shared. Respected.

My wounds, my commitments

I encountered social barriers that left me speechless... then pushed me to speak out louder. One day, at a train station, a man wanted to ask me for help with his ticket. But his wife stopped him. She preferred to ask someone else. As if receiving my help would have tainted her.

Other times, it's the stares. Heavy, insistent, as if the simple fact of wearing a veil exposed me. As if my headscarf, instead of protecting my privacy, revealed a difference that was disturbing.

There was that time when a cyclist started singing “Douce France” as he passed me, his eyes fixed on me. Why? Perhaps to remind me that this country was not mine. Yet I was born here. I am French. I wear the veil whether he likes it or not.

Another time, while crossing a pedestrian crossing, a driver slowed down, looked me up and down... then suddenly accelerated, blasting music with racist lyrics. As if to say to me: “You don't belong here.”

In Dijon, I am struck by anxiety about employment: they say that “women who wear veils don't get hired.” I want to reconcile my beliefs and corporate values, not trade one for the other. Wearing a veil means covering my body, not my ideas. My eyes are not veiled: they see the harshness of judgments and the tenderness of allies. I write so that others don't have to justify themselves before they can exist.

But what has affected me most is in sports. A space that should bring people together. A teacher isolated me, pinned me against a wall, and told me that my veil was not in line with “the values of sport.” What values? Hers? She told me that I wouldn't be able to see my sides to play badminton. Then she uttered the words that froze me:

“Take off your veil.”

I had come to spend time with my friends, not to justify my presence. I felt humiliated. But I kept my cool. Because I knew that if I said anything too strong, I would be labeled: “Muslims are savages, they don't respect the rules.” Or the Muslim woman who loses her temper. ." I understood that they weren't demanding neutrality, they were demanding my erasure. So I decided to stop speaking softly. This battle wasn't just about me. It was about all those who might not have had the strength to respond.

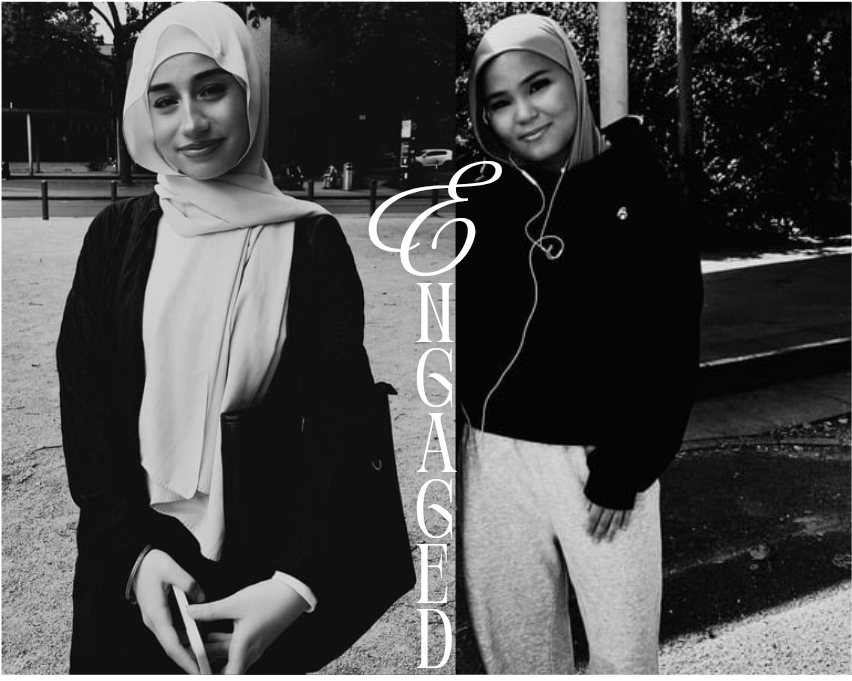

In Mainz, I encountered voices that resonate with me.

“We are referred to as a minority, but our lives are not a footnote. My freedom begins when people stop speaking for me.”

— Yasemin, a veiled student in Mainz

"The veil is not a criterion for competence. In my company, I reviewed the recruitment criteria: we evaluate evidence of talent, not symbols."

— Hannah, HR project manager in Mainz

"Filming veiled women who create, run, care for others, teach... that's my antidote. The right image corrects the distorted narrative."

— Zahra, freelance videographer in Mainz

Their words are clear: to be heard, we need open doors and microphones held at face level, not above our heads.

What the research says is consistent with what my experiences tell me. An experimental study by Gustave Eiffel University shows that wearing a headscarf reduces the likelihood of getting an interview for an apprenticeship contract, even with comparable qualifications; the discrimination is clear and measurable.

How to make our voices heard

Making the voices of veiled women heard does not require a battle, but rather confident and well-targeted actions. First, the law must protect without suffocating: if France clarified that the “neutrality” of public services does not mean “erasure” or exclusion, it would pave the way for genuine equality of access to internships, apprenticeships, and clubs. Targeted training sessions for HR on implicit bias, combined with cross-border mentoring programs between Dijon and Mainz, could enable veiled students to envision sustainable—and visible—careers. In sports, the model already exists: approved equipment, such as the “sports hijabs” tested in Germany, could be rolled out across France, with other groups such as Les Hijabeuses, created in May 2020 to defend the right of female soccer players to wear the veil during official matches in France, organizing open days promoting the slogan “Come as you are, play as you want.” In the media, following the golden rule of “Nothing about us without us” means inviting veiled women to be sources, not objects: a TV show, an interview on science, economics, or culture—not just on the veil. At university, supervised workshops on secularism in practice, combined with alert cells with a trusted third party, open up a space where speaking up carries less risk. Finally, culture can overturn narratives: create creative residencies (photos, podcasts, videos) that tell the story of Dijon or Mainz as we see it, or organize traveling exhibitions under the title “Voices covered, eyes uncovered,” to remind people that the veil does not cover—it reveals.

These solutions require neither heroism nor permission: just the will to do so.

I move forward because others are moving forward too. The names vary, the cities change, but the same phrase keeps coming back: “We are not a parenthesis in the Republic or a margin of Europe.” We are full citizens. The veil is not a wall: it is a text that everyone thinks they can read without us. So I take up my pen.

I make you a simple promise: I will continue to write, film, and interview these women—in Mainz today, in Dijon tomorrow—so that our stories cease to be isolated cases and become references. I will go and see Yasemin at the university library, Hannah at lunch break, Zahra between shoots. I will note their hesitations and their pride, their job rejections and their tiny victories, so that statistics finally meet faces. Being veiled does not mean hiding your ideas.It means raising them even higher, because too often, people try to silence us.

Because deep down, dear future, my voice is not just mine. It carries all those who still hope to be heard. And if I am writing all this today, it is so that I will remember it in ten years' time: the world I imagine begins with the words I write today.

Text : Dina Kadouri / Images : D.R.