Politically active on social media, politically active in the streets

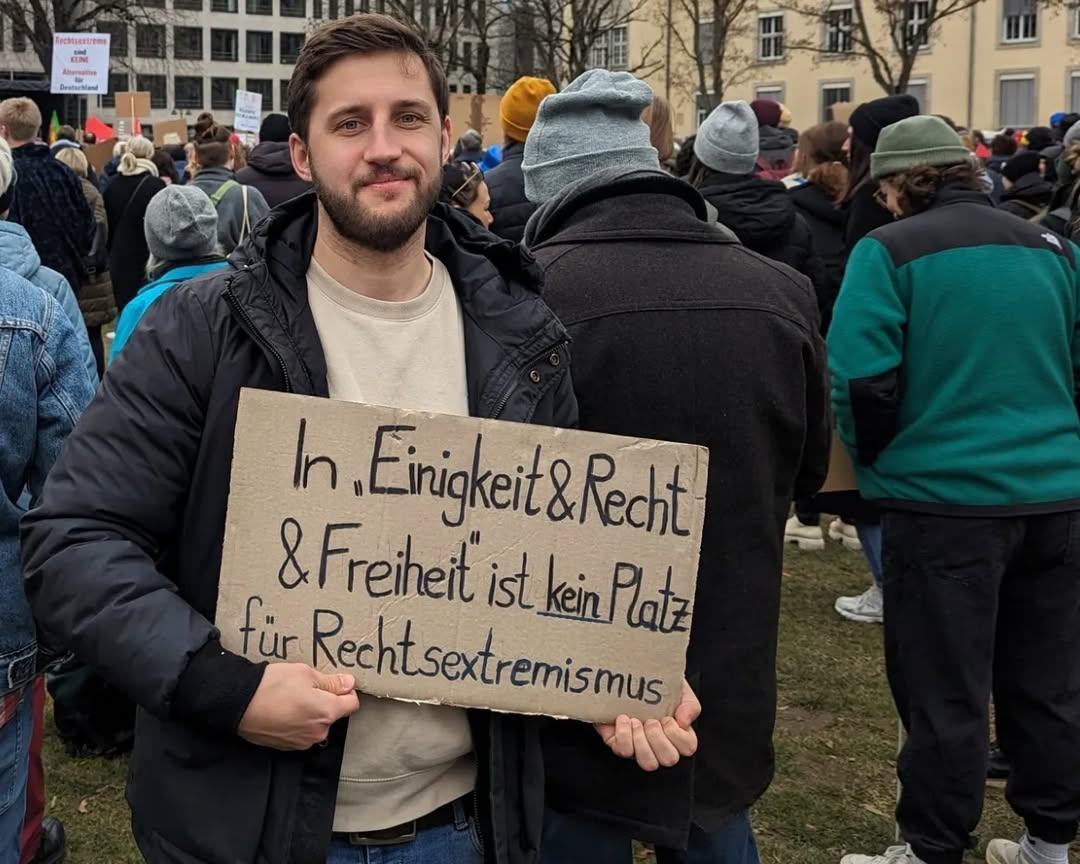

Political engagement can take many forms — whether in the streets of Mainz, Germany with the group Omas gegen Rechts or on Instagram with Katarina and Niklas. All of them have made it their mission to stand up for democracy and to resist its enemies.

The 1968 movement in Germany was relatively small, but the demonstrators were angry, they were loud, and they wanted to be heard. Today, many activists are found on social media – content spreads quickly and even though there are restrictions, is often difficult to restrict. How does access to social media change the way political opinions and topics are shared and how people get involved?

Nowadays, when we share all our questions, concerns, fears, worries, activities, and everyday events on social media, we have to ask ourselves: how does this affect our society? What does it mean to share everything with a chatbot, to post videos online without knowing who is watching them or what they will do with them? Not knowing whether our personal topics will be taken seriously or misused? Anyone can post anything at any time, day or night. We all know how important it is to exchange ideas, to get involved, and to stand up for a functioning democracy.

"Protests create images that don't exist in the digital spaces"

In recent years, the number of internet users has steadily increased, as has the number of people who get their information exclusively from the internet. Approximately 53% of Germans under the age of 30 use the internet as their primary source of information when it comes to topics such as politics, elections, and other societal issues. They also engage in discussions on a wide variety of topics.

Katarina is a young student and runs the Instagram channel @verstehe_politik, where she shares content about politics. She always was aware of the issue of disinformation on the internet. During a Science Slam she learned how important it is to provide people with accurate information before they come across false narratives. She began searching on social media: “I had been very into social media for a long time and started looking at what was available on Instagram. There was surprisingly little in this area, so I started the channel,” she explains.

On her channel, she wants to inform people about politics so they can form their own opinions. But it’s not just about political issues for her — she also aims to promote values such as openness and tolerance, enabling more empathetic interactions. Her followers can exchange ideas in the comments, and she regularly gets invited to small events to facilitate direct dialogue. “In the comments, people mostly interact with each other. Many in my community seem open to different arguments and are genuinely interested in other opinions.” However, when a video goes viral and leaves the usual social media 'bubble', the tone in the comments tends to get rougher. People often just want to get their point across — not necessarily engage in dialogue. She also often receives private messages from people seeking conversation or answers.

Katarina is also active on the streets. Being in the middle of a demonstration, standing with many people fighting for the same cause, creates a sense of community. The same goes for Inge Dietrich, who is now active in the group Omas gegen Rechts (Grandmas Against the Right), advocating for democracy. Inge has always been politically engaged and was part of the 1968 movement as a young woman. “Those were very angry protests.” Young adults had dreams and hopes, and the young democracy gave them the freedom to take to the streets for those “fights.” “We weren’t afraid of the mounted police, nor of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, which was also dominated by the far right — we weren’t afraid of anything, really.”

The ‘68 movement arose rather spontaneously. In the beginning, participation numbers were relatively small — around 20,000 people, according to the Süddeutsche Zeitung — but the demonstrators were determined. They wanted to be heard and wouldn’t back down. Inge adds: “That desire for change was so strong in us — I felt like it carried us. We didn’t really think about the consequences. We just tried to live that desire for change in our daily lives.”

Young adults had dreams and hopes, and the young democracy gave them the freedom to take to the street for those "fights"

In recent years, the number of people participating in demonstrations in Germany has been rising again, with large-scale protests becoming more frequent. One example is the 2018 protest in Berlin, where, according to the Süddeutsche Zeitung, 240,000 people demonstrated for an open society. People of all ages are taking to the streets in Germany. The topics they care about may differ depending on age group – but they don’t have to. Studies on the themes of protests show that the focus has shifted over time. In the 1960s, protests were mainly about democracy and environmental protection. In the 1970s, peace and opposition to the NATO Double-Track Decision became central topics. Later on, migration, ethnic minorities, and globalization gained importance. So there are always phases in which certain issues come to the forefront more than others.

No matter the topic, people go to protests to be heard and to draw attention to their cause. The same is true for videos posted online – no matter the platform. Niklas runs an Instagram channel (@otto.wels), where he started in 2021 by commenting on politics and the upcoming election campaign in Germany. To his surprise, his success and the reach of his content were greater than expected. Since then, he has used that reach primarily to support the people of Ukraine in their fight for freedom and to raise donations. His success has even drawn the attention of politicians, some of whom now support his activism. But Niklas isn’t only active on social media – he also takes to the streets.

“Protests create images that don’t exist in the digital space,” he states clearly, adding: “That way, people who aren’t involved can see much more clearly how passionate others are about a cause. Sure, someone like Sahra Wagenknecht (leader of the party Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht – Vernunft und Gerechtigkeit) might rack up hundreds of thousands of views and likes online. But fewer than 10,000 people show up at her protests.” If the support shown online cannot be translated into real-world action, then it has no real impact. That’s why it's important for online activists to also connect offline and show their faces.

For Niklas, it’s crucial to both share content online and interact directly with people — whether at protests or in one-on-one conversations: “I wouldn’t draw a strict line between social media and activism ‘outside’ of it. Social media influences real life.” The group Omas gegen Rechts agrees. In our conversation, they emphasized how both the physical act of demonstrating and a strong online presence are important.

Like Katarina, Niklas also experiences a high level of engagement with his Instagram community. Unfortunately, he doesn’t always receive support – he’s also faced hostility and even death threats: “But that doesn’t get to me. As democrats, we must never allow ourselves to be intimidated. We must always stand up to the enemies of freedom.” The fact that everyone – even those “enemies” – can express and spread their opinions online is part of what democracy means. “Still, I see social media as an opportunity overall – but we must take the dangers of manipulation and propaganda seriously.” Fake news plays a key role here, too. It’s not enough to just flag false information: “We need to start teaching media literacy much earlier. There’s still a lot of work to do.”

Political engagement can take many forms. But the most important thing is to speak up — something Inge finds especially important: “Democracy depends on exchange. Only then something can evolve. And a democracy that doesn’t evolve is, in my opinion, dead.” Whether we’re marching in the streets, connecting with others during protests, or engaging in discussions on online platforms — anything is better than doing nothing. “If you do nothing, that’s the only real mistake you can make — and it’s a fundamental one.”

Text : Julia Gaul / Photos : D.R.